Heroes and Villains No. 1. William Banting.

like beans to a horse, whose common ordinary food is hay and corn … human beans [are] bread… sugar, beer and potatoes

London, 1860s: Mr William Banting, a very successful London undertaker, was fat and fed up. He was not a happy man. His health was suffering; he could no longer reach down to tie his own shoelaces. He desperately wanted to lose weight but no matter how many medical men he consulted, nothing worked. Even vigorous exercise had no effect; he got fit but stayed fat. But his luck changed on the day he consulted one Mr William Harvey, an Ear, Nose and Throat surgeon. Harvey had, in turn, been influenced by Claude Bernard, an eminent French physician and expert in diabetes. Based on Bernard’s ideas Harvey devised a diet he hoped might help with obesity. Banting listened; he followed Harvey’s advice, and at last, began to lose weight. His health improved. He was delighted. So delighted was Banting with his success that he felt compelled to share his insight with others. After all, with the exception of Harvey, all the doctors he had consulted had been of no help at all.

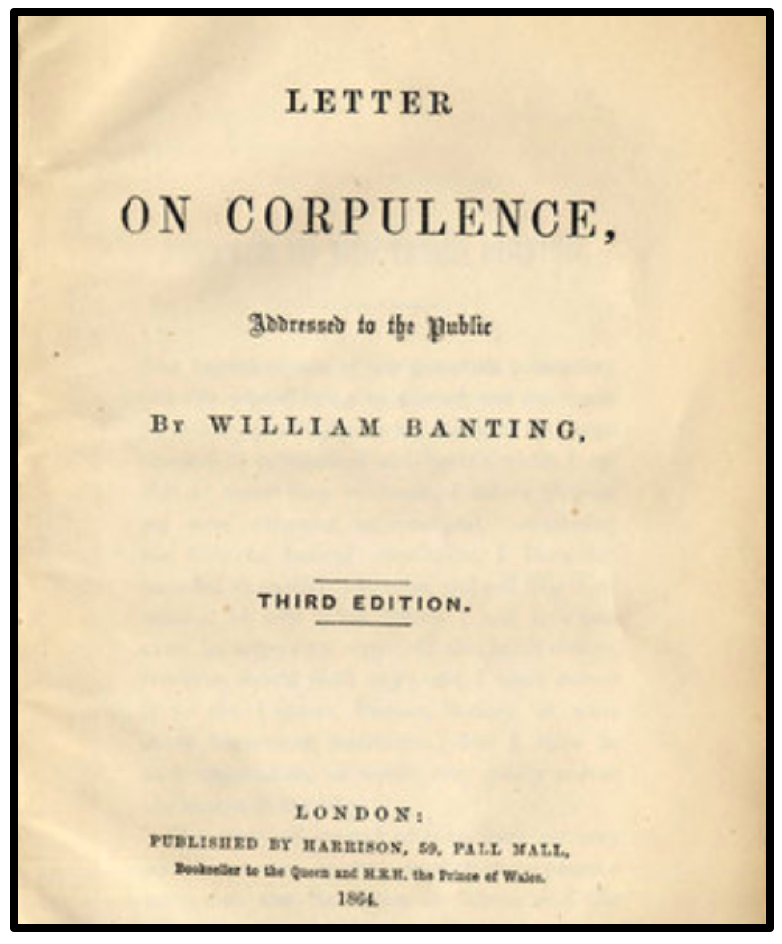

So, Banting wrote and published a short pamphlet entitled a Letter on the Corpulence. His advice was brief; he identified a few forbidden foods, “like beans to a horse, whose common ordinary food is hay and corn … human beans [are] bread… sugar, beer and potatoes”. This one line was virtually the only advice he gave. The Banting method became, for a while, all the rage. European Royal households started to Bant’. It worked. Everyone was impressed; everyone except of course the medical establishment, who ironically had nothing effective to offer. ‘How dare an uneducated man give health advice?’ complained a letter to the British Medical Journal. ‘He should mind his own business’; professional jealousy. When Banting’s Letter was published there was no officially sanctioned diet. The diet-industry only started getting into its stride a century later. But there had always been a tradition of healthy, indeed healthful, scepticism with science in general and until recently nutrition in particular. The Victorian version of the standard diet with its established food conventions for the affluent had failed Banting. But he found something else, something that succeeded. Could it perhaps succeed again today?

So, Banting wrote and published a short pamphlet entitled a Letter on the Corpulence. His advice was brief; he identified a few forbidden foods, “like beans to a horse, whose common ordinary food is hay and corn … human beans [are] bread… sugar, beer and potatoes”. This one line was virtually the only advice he gave. The Banting method became, for a while, all the rage. European Royal households started to Bant’. It worked. Everyone was impressed; everyone except of course the medical establishment, who ironically had nothing effective to offer. ‘How dare an uneducated man give health advice?’ complained a letter to the British Medical Journal. ‘He should mind his own business’; professional jealousy. When Banting’s Letter was published there was no officially sanctioned diet. The diet-industry only started getting into its stride a century later. But there had always been a tradition of healthy, indeed healthful, scepticism with science in general and until recently nutrition in particular. The Victorian version of the standard diet with its established food conventions for the affluent had failed Banting. But he found something else, something that succeeded. Could it perhaps succeed again today?

This is the first is a series of short essays. Whether the subject is a villain or a hero is for you to decide. Future subjects will include Banting’s namesake Frederick, Thomas (Peter) Cleave, Elliott Joslin, William Osler, John Yudkin, Lulu Hunt-Peters, Ancel Keys and his lovely wife Margaret, Elsie Widdowson, and Vilhjamur Stefansson.

(picture credit: Wikipedia)